Death, addiction, law suits… Through all the trials and tribulations, Metallica have somehow survived over 35 years on hard rock’s relentless road. The youthful fire which scorched a blazing path through the metal scene back in the early 1980’s still burns brightly despite all four members now being in their fifties. Here JAMES HETFIELD and LARS ULRICH talk about how Metallica evolved from wild-eyed thrash punks to one of the biggest bands on the planet.

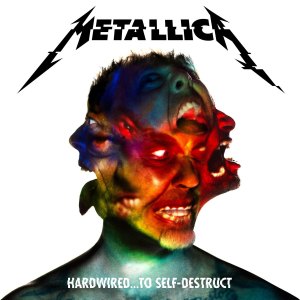

You celebrated your sixth number one album in November when your latest record, Hardwired…to Self-Destruct, topped the charts around the world. After all your success, do you still get a kick from that happening?

James: Oh man…for sure! But you know, it’s bizarre, and very surprising, yes. The older we get, the more special getting a number one album is going to get. After 35 years, that this can still happen, it’s great. It’s the oxygen we need, being in a band and playing music, so we get to live a little longer!

Lars: Even now when we put out a record, you never know what to expect. These are changing times in music so having a number one record in all these wonderful countries is an amazing thing. Obviously, we’d prefer to release records that people like rather than not but having number one records is not why we get out of bed in the morning. We want to make music for people to enjoy and if it’s successful then that’s a bonus. But you know what, the fact that Metallica can still release records that matter to people is a great thing, that hard music still matters to people is a great thing. I feel like rock groups are becoming a minority these days. There are fewer and fewer bands that a doing well on a global scale so being one of them is a privilege. It’s a good time to be in Metallica.

Hardwired… was the first album to be released on your own Blackened Recordings label. How different was this experience compared to others?

James: It wasn’t that different at all. We went about this with the same process as we have every single time. I would say, that as it was on our own label – which is just our own label in the US, we’re still on Universal in the rest of the world – we were able to take our time, to start writing without deadlines, no one saying ‘ hey, we need it by this time.’ That was maybe the only thing which was unusual from previous albums.

James: It wasn’t that different at all. We went about this with the same process as we have every single time. I would say, that as it was on our own label – which is just our own label in the US, we’re still on Universal in the rest of the world – we were able to take our time, to start writing without deadlines, no one saying ‘ hey, we need it by this time.’ That was maybe the only thing which was unusual from previous albums.

Lars: The main difference was not in the recording of it but what happened on the day immediately after we were finished because we now have to do 90% of the work ourselves whereas 10 or 20 years ago, other people and other companies did most of the work. We have a much bigger infrastructure now and all these people who, for better or worse, answer to the band members rather than a CEO so we have a different post-recording set up.

Part of that set-up is being responsible for your own master recordings, which now belong to you. How did that come about?

Lars: Back in the early 90s, Cliff, one of our managers, was talking about this amazing place of total independence and creative freedom which would come from owning your own master recordings. It would offer us a total disassociation from the music business. When that was explained to us, it obviously made a lot of sense. So when we entered into contract negotiations, that was always the primary modus operandi, to eventually own our back catalogue. Any disassociation and dynamic which releases you is a great thing because you are truly free to do what you want.

James: Elektra were a good fit for us but we always wanted to own our own masters at some point – and why wouldn’t you? It’s really great to own them because they’re ours after all! A lot of bands from the 70s and 80s did not see that as an option or even care about it. We’re fortunate to have had some pretty savvy business management.

That shows a lot of foresight, to look ahead and to plan stages of your career way in the future. Did you have some idea at the time that the music industry was going to change so dramatically?

James: Hell no! We had no clue. I don’t think anyone did. At the time, the labels were like banks; you loaned them your music and they gave you money so you could tour or do whatever you wanted with it. They paid you up front, that’s pretty much how it was. We knew it would be great to own our masters but we had no idea what was going to happen with the industry.

Do you have any plans to delve back in and re-release material?

James: We’re definitely going remaster the back catalogue. We’ve always been very instrumental in the sonics, how our music sounds. That’s very important to us. Obviously there are some records that sound better than others. The soundtrack to the film Through the Never sounded great and Hardwired… also sounds fantastic. We’re very happy with (Hardwired… producer)Greg Fidelman and his sonics. So he’s going through the back catalogue and he’ll remaster them. Along with the re-releasing, we’ll try and make them all very special packages. But these days, what do you do? What hasn’t been done by someone else? There are special editions with this and that… I guess we’re on a pretty nostalgic trip these days with the Rock’n’Roll Hall of Fame, the Master of Puppets book, revisiting the old records. So these remasters will come out with a lot of cool stuff, nostalgic pictures and stories we’ll dig up.

James: We’re definitely going remaster the back catalogue. We’ve always been very instrumental in the sonics, how our music sounds. That’s very important to us. Obviously there are some records that sound better than others. The soundtrack to the film Through the Never sounded great and Hardwired… also sounds fantastic. We’re very happy with (Hardwired… producer)Greg Fidelman and his sonics. So he’s going through the back catalogue and he’ll remaster them. Along with the re-releasing, we’ll try and make them all very special packages. But these days, what do you do? What hasn’t been done by someone else? There are special editions with this and that… I guess we’re on a pretty nostalgic trip these days with the Rock’n’Roll Hall of Fame, the Master of Puppets book, revisiting the old records. So these remasters will come out with a lot of cool stuff, nostalgic pictures and stories we’ll dig up.

When looking back at your back catalogue, do you have any favourites or regrets? Any records where you now think, ‘what the hell were we thinking?’

James: There are things I would like to change on some of the records but it gives them so much character and such uniqueness that you can’t change them. I find it a little frustrating when bands re-record classic albums with pretty much the same songs and everything, and then have it replacing the original. It kinda erases that piece of history. These records are a product of a certain time in life, in the career of the band; they’re snapshots of history and they’re part of our story. Okay, so And Justice for All could use a little more low end and St. Anger could use a little less tin snare drum but those things are what make those records part of our history. So, no regrets.

Metallica started out in another age, when vinyl was god. You now have your own vinyl printing plant in Germany. Will you be joining the campaign to restore the format to its former glories?

James: Just because we grew up with and love vinyl, it doesn’t mean it’s the only and best format for us. We’re champions of getting music out any way and any how. Like Lars said, there are still fans who want to buy our music on record so we’ll cater for that but we’re excited by the challenges the digital world sets us and we like to be challenged. Saying that, I do love vinyl. It’s an experience, an event. It’s very tangible. You hold the record, take it from the sleeve, place the needle on the groove. About six months ago I was in Los Angeles visiting some old high school buddies and we just sat around, listening to vinyl…stuff like Kansas. Just the act of flicking through the boxes, smelling the cardboard, reading the sleeve notes, and listening to that warm sound. It’s a very immersive experience.

So, you’re essentially your own bosses now. Would you say it’s been a natural progression, to evolve from crazy kids with guitars to rock stars-slash-businessmen?

Lars: I’d like to think that we’re still crazy adults, still trying to figure it all out. When I look in the mirror, I don’t see a businessman but obviously when you have an organisation and bunch of people who work for you, there’s a point where you at least have to act mature. I think we do our best and I think we have a pretty decent balance in terms of how those two sides of us play out. I think it’s possible to wear those two hats but not necessarily at the same time. We have a trusted group of people who we’ve worked with for a long time who advise us on how we connect the dots, which is an invaluable thing to have. I’m 52 now, but I still feel like that crazy kid, trying to work out what’s going on at times so to have a trusted team behind us, having our own set up and being fiercely independent like Metallica is, that’s really a cool thing which we’re very proud of.

Lars: I’d like to think that we’re still crazy adults, still trying to figure it all out. When I look in the mirror, I don’t see a businessman but obviously when you have an organisation and bunch of people who work for you, there’s a point where you at least have to act mature. I think we do our best and I think we have a pretty decent balance in terms of how those two sides of us play out. I think it’s possible to wear those two hats but not necessarily at the same time. We have a trusted group of people who we’ve worked with for a long time who advise us on how we connect the dots, which is an invaluable thing to have. I’m 52 now, but I still feel like that crazy kid, trying to work out what’s going on at times so to have a trusted team behind us, having our own set up and being fiercely independent like Metallica is, that’s really a cool thing which we’re very proud of.

James: Lars is the more business-savvy guy and I’ve been extremely fortunate to have been partnered with him in this thing for 35 years. He followed Motorhead around, he followed Diamondhead around, learning from them and other bands; how they did things, why they made the decisions they made, why is one manager better than another. He is just very inquisitive when it comes to the business side of things. To have someone with that drive and quest for knowledge, that’s been invaluable. Me? I just…didn’t want a job! I wanted to play music, create and have my therapy and career wrapped into one! So it’s good to learn from others and apply that to your own life and path but you know, deep down, we’re still rebels, we’re still risk takers, we like being challenged by life and being faced with the question ‘what do we do next with this gift we have?’ Planning and preparation is only part of it. Guts, soul and fire are also invaluable weapons.

I find it hard to imagine Metallica sitting around in glass-walled offices shouting into phones with ties askew like in some HBO corporate drama…

James: There are no ties, man, and we’re very rarely in an office. As for shouting into phones, we pay people to do that. I think the bigger picture is about who’s in control, who’s running the ship and who’s just having a good time being in the band. It might be fairly obvious but Lars and I have been the two guys who put this band together; we formed this thing from day one and have had this vision. We’ve been in the driving seat but Kurt and Rob are always ready to go with us wherever this ride takes us, they’re always willing, always up for the challenge, and we’re all excited about where we’re heading.

You’ve always been fiercely proud of your independence. How important do you think being independent and remaining true to your own vision is to having a long and successful career?

James: For us, yes it has been important but for other people? I don’t know. Back in the day, when we were starting out, getting signed by a label was a huge thing. I don’t think that’s such a huge thing now. The fact that you can make your own music in your basement and press it and put it out yourself is wonderful but how far do you get with that? Do you eventually sign up with someone who’s bigger? These are all different business decision you need to make. You need to ask yourself ‘what is it we want to do?’ Do you want to tour the world, stay local? You should do what makes you happy.

James: For us, yes it has been important but for other people? I don’t know. Back in the day, when we were starting out, getting signed by a label was a huge thing. I don’t think that’s such a huge thing now. The fact that you can make your own music in your basement and press it and put it out yourself is wonderful but how far do you get with that? Do you eventually sign up with someone who’s bigger? These are all different business decision you need to make. You need to ask yourself ‘what is it we want to do?’ Do you want to tour the world, stay local? You should do what makes you happy.

Lars: We’ve always felt that we were outsiders, that we never really belonged to anything so even when we became successful, we still felt like successful outsiders. I guess we never really felt the need to play the game. The best thing about our success is that it has afforded us the opportunity to carve our own creative path. I’ll always be incredibly thankful for that. Primarily, independence for us means that we’ve never really taken money from anybody; we’ve never owed anybody anything. Our managers from very early on protected us from being in debt to anyone. As James said, when we started out record companies were like banks. You had to take money to make records, and then repay what it cost to produce that from your profits. And that’s something we’ve never really had to do so we’ve been pretty appreciative of that.

I imagine being flexible and adaptable also helps in maintaining a career. You’ve seen a lot of changes since you started out, especially with the dawn of the Internet age. How has Metallica coped with the shift to a digital world?

Lars: We’ve adapted quite well, thanks for asking! We’re sat here surrounded by technology linking us to the world, and Metallica’s music is available on numerous digital and streaming platforms and formats. I think that’s very cool. But you have to remember that there are places on this beautiful planet where people still buy CDs or vinyl, so for every move you make in the digital world, there are still fans who are still more traditional in the way they buy and listen to your music. Living in San Francisco where we’re surrounded by all the latest technology, you have to remember that there are other places in the world where the more traditional formats are still the way to go.

James: We’ve always been control freaks. As artists we’ve always felt the need to have at least some control over how our art is presented. Whether you’re an artist or a sculpture, looking to place your painting or sculpture in a gallery or museum, you’re going to have a strong opinion on how it’s hung or where it’s placed because that’s part of the artistic vision. We’ve always felt the same way. So when the floodgates opened and music was all over the internet, going for free, it scared us for sure and we didn’t know what to think about that but obviously now, it’s a great and convenient way to get your music so adapting to it is the only way to survive. I think that’s true for anyone in any walk of life. We do our best in the digital world; with Hardwired… we released a song at a time, a video at a time, a video for each song, and that works in this era. We like to surprise people and it’s hard to surprise people these days but the Internet gives us new ways to do this. It’s a new creative challenge.

The topic of free music on the Internet must be a thorny issue for Metallica, given the legal issues you had with peer-to-peer file sharing service Napster at the turn of the millennium. Do you feel that you were unfairly treated or misrepresented during that case?

James: The way people saw us then was beyond our control. What people think about us, about me, is none of my business. I knew it was the right thing to do, and as I said, it is a great and convenient way of getting music but I wish the record companies had not embraced it as much as they did and I wish it had unfolded in a different way but we couldn’t control that. The way we were portrayed…Well, we were an easy target. Someone who is established and who is concerned about their art is there to be shot at. Other artists came up to us and said that they supported what we were doing and were proud that we were sticking up for them but they would not come out of the shadows to help us. That left a bitter taste.

James: The way people saw us then was beyond our control. What people think about us, about me, is none of my business. I knew it was the right thing to do, and as I said, it is a great and convenient way of getting music but I wish the record companies had not embraced it as much as they did and I wish it had unfolded in a different way but we couldn’t control that. The way we were portrayed…Well, we were an easy target. Someone who is established and who is concerned about their art is there to be shot at. Other artists came up to us and said that they supported what we were doing and were proud that we were sticking up for them but they would not come out of the shadows to help us. That left a bitter taste.

Lars: It was a street fight and the other guys painted this picture that it was between Metallica and their fans, and Metallica against downloading which it really wasn’t. It wasn’t about downloading, it was about choice. If I want to give away my music for free, whose choice is that? Is it my choice or someone else’s choice? So as it’s my music, I would presume it was my choice. But that choice was taken away from us. That was the real issue but they made it about us versus our fans which was a really smart move because it made us the bad guys. I do think we were misrepresented but we should have seen that coming. It was a strange summer, that’s for sure.

That strange summer included a South Park episode portraying you, Lars, crying by your pool because you could no longer afford to have a gold-plated shark tank bar installed due to people illegally downloading Metallica’s music.

Lars: That has floated across my eyeballs, yes.

And?

Lars: I’m a pretty thick-skinned person and we took a lot of hits that summer, and that was one of them. Everyone had an opinion, and it was a little weird, let’s leave it at that! Sometimes bad press is better than no press, right? Anyway we survived to fight another day.

James: South Park is no stranger to taking the piss out of anybody. I love it. It’s great to laugh at yourself. If anyone thinks of Lars that way, that’s up to them.

So you never fancied having a gold-plated shark tank bar then?

James: We’re pretty practical people. You look at us and we’re not too image conscious. We’ll put our money into a stage set or a good production or something, like making a movie. The money we’ve made from this has been reinvested in the band, for trying and exploring new things. As far as decadence goes, there’s none of that. We’d kick each other’s asses. That doesn’t fit the Metallica mould whatsoever.

The Napster case was just one of many tough times the band has been through. What’s the closest you’ve ever come to splitting up?

Lars: I would say that during period around the Some Kind of Monster documentary where it shows James going away to rehab and taking a year out of Metallica to figure out some things on his own. When he came back from that year away with a new set of tools for engaging and interacting with us, I wasn’t sure for the first six months how that was going to work out because I wasn’t sure I could adhere to those particular ways. It took a couple of years for things to really settle but we found the right balances and by the time the St Anger cycle was over in 2004 it had kinda fallen into a functional dynamic. We’ve had the best ten years together since then, when it all fell back into place around 2005 and 2006, and we really appreciate each other and what we have so it worked out but it was pretty ropey there for a while. We weren’t quite sure what was going to happen. I’m not a big fan of the ‘what if,’ questions because who knows what would have happened if we had split. If you turn left or turn right, things could work out differently. But we’re here, we’re talking to you and Hardwired… is out in the world. Trying to imagine a world where Metallica split ten years or so ago is a waste of energy.

Lars: I would say that during period around the Some Kind of Monster documentary where it shows James going away to rehab and taking a year out of Metallica to figure out some things on his own. When he came back from that year away with a new set of tools for engaging and interacting with us, I wasn’t sure for the first six months how that was going to work out because I wasn’t sure I could adhere to those particular ways. It took a couple of years for things to really settle but we found the right balances and by the time the St Anger cycle was over in 2004 it had kinda fallen into a functional dynamic. We’ve had the best ten years together since then, when it all fell back into place around 2005 and 2006, and we really appreciate each other and what we have so it worked out but it was pretty ropey there for a while. We weren’t quite sure what was going to happen. I’m not a big fan of the ‘what if,’ questions because who knows what would have happened if we had split. If you turn left or turn right, things could work out differently. But we’re here, we’re talking to you and Hardwired… is out in the world. Trying to imagine a world where Metallica split ten years or so ago is a waste of energy.

At least by staying together you’ve avoided the tedious line of questioning about reforming. It seems to be the fashionable thing these days for defunct bands to get back together.

Lars: There are lot of bands that reform for a lot of different reasons and since I don’t know the internal dynamics, it’s hard to comment on. There could be someone who says ‘I’m reforming this band for $20 million’ and I’d say ‘good on ya!’ Who the hell am I to say that you shouldn’t do that. I can barely keep my own shit together! The world doesn’t need another person being critical of someone else’s decisions.

The Oasis documentary ‘Supersonic’ has increased the chatter on the Internet about whether Oasis will reform. As a friend of Noel Gallagher and fan of the band, what’s your take on the rumours, Lars?

Lars: There may be a lot of talk on the Internet about Oasis getting back together but I don’t think there’s a lot of talk in Noel Gallagher’s head about that. Just imagine if you were Noel Gallagher and every interviewer asks you about whether Oasis are getting back together. Could you imagine how fucking annoying that must be? That would drive me fucking batshit crazy! I don’t think it’ll happen. From what I see he seems perfectly content doing what he’s doing and I think what he’s doing is great. If he is going to reform Oasis, I’m pretty sure I won’t be the first one he asks for advice.

Lars: There may be a lot of talk on the Internet about Oasis getting back together but I don’t think there’s a lot of talk in Noel Gallagher’s head about that. Just imagine if you were Noel Gallagher and every interviewer asks you about whether Oasis are getting back together. Could you imagine how fucking annoying that must be? That would drive me fucking batshit crazy! I don’t think it’ll happen. From what I see he seems perfectly content doing what he’s doing and I think what he’s doing is great. If he is going to reform Oasis, I’m pretty sure I won’t be the first one he asks for advice.

The scenes of Oasis at Knebworth, playing to 250,000 fans over two days are very impressive but that pales into insignificance when put next to Metallica’s Tushino Airfield show in Moscow in 1991 where an estimated 1.6 million people attended.

James: Everybody you talk to about that show will give you a different figure of how many attended but I can tell you that there was a fuck of a lot of people! It was crazy. That was a wild afternoon, I can tell you.

Lars: Big shows like that are insane and it never becomes normal playing to such huge crowds. But I love playing stadiums, I love playing festivals, I love playing small theatres… I just love playing live to people. We’re lucky to be able to play the full range of venues and to have that choice is a privilege. The day any of it becomes normal, you have my permission to come and slap me around the head a little bit. I think the older I get, the more my eyes open to see how amazing this all is. You know, it’s 35 years since we started and this amount of people still care and still roll along for the ride.

On the topic of touring, you’ve made it clear that that from now on you won’t be going out for the long-haul but will play for two weeks and then have two weeks off to spend with your families. Does it get easier to juggle family life with the music career as you get older?

James: It does. We’re extremely fortunate to be where we are. To be able to do two weeks on, two weeks off is really great. Not only for our families but for our own sanity, and our own physical, mental and spiritual well-being. We need to do that. We can’t tour like we did in our 20s, that’s for sure. It needs to be age-appropriate touring for us these days. Whatever it takes for us to get on the stage, have fun and be at 110%, that’s what we’ll do.

I bet your families will be happy to see more of you.

James: You’d have to ask them! I’m totally into embarrassing my kids; wherever, whenever, as much as possible. I’ve got three teenagers now and life’s a little different. I’m very involved in their lives and I love each and every one of them to death and really want their dreams to be realised, and hopefully be part of those dreams. I try not to hover too much, enable them too much, allow them to struggle when they have to struggle. I’m less strict than my wife but we’re a great team; I learn from her, she learns from me. We definitely have different parenting skills but I think the kids benefit from both.

James: You’d have to ask them! I’m totally into embarrassing my kids; wherever, whenever, as much as possible. I’ve got three teenagers now and life’s a little different. I’m very involved in their lives and I love each and every one of them to death and really want their dreams to be realised, and hopefully be part of those dreams. I try not to hover too much, enable them too much, allow them to struggle when they have to struggle. I’m less strict than my wife but we’re a great team; I learn from her, she learns from me. We definitely have different parenting skills but I think the kids benefit from both.

And you’ll get some time to yourself? Maybe do a little skateboarding, James?

It’s been a while since I’ve been on a board, man. We played the House of Vans in London at the end of last year and that was very cool to see those kids doing their thing. Some of the crew had a go but those days are done for me, for sure. I’ve got other passions now. We all need ‘you’ time. You need to get away. There’s still a lone wolf in me who loves solitude, loves going solo whether it’s music, hunting, hiking or camping, whatever – just getting out on my own. Or getting in the garage and tinkering with something, getting really detailed and lost in a project, I love doing that.

How to become a rock star in 2016: Three tips by Lars Ulrich

Find like-minded people like yourselves who are passionate

We’re all very different characters but at the core of it, we’re a band that have been going forward together. James and I are perhaps at the steering wheel with Kirk and Rob sitting in the back but we all get a say in where we’re going. We’ve seen band members come and go but even those who are not with us now have shared the passion of being in Metallica. Passion means you’ll fight about stuff from time to time but you’ll be fighting for the good of the band. Finding people ready to do that, to get in the trenches with you and go the distance, that’s the solid base you need.

Stay true to your own vision and ideals

We’ve made choices and music that have not always been popular with everyone but you know, that’s not really why we make these choices. We’ve done what we’ve done because we’ve believed in every single part of it. If we always made music to a template of what has brought us success in the past, we would sound the same and never progress, and that would be like a kind of creative death. We could just slip the same record into a different sleeve and take the rest of the year off. We welcome challenges and set ourselves challenges to keep things interesting for everyone involved. People will try and tell you to go another way and will sell it as the best thing for the band, but you – the band – should be the only ones making those decisions. Don’t let anybody talk you out of them. Listen to those you trust but stand firm together.

Stay committed

Stay the course. Hang in there. If you’re talented, someone will find you.

This article first appeared in an edited form in The Red Bulletin Magazine.